Allergy Treatment

Allergies are one of the world’s most common chronic health conditions, ranging from mild hay fever to more severe food-related allergies.

This guide will explore different types of allergies, testing and diagnosis, and treatment options. Additionally, we will discuss some lifestyle and environmental modifications one can make to enhance their quality of life while dealing with allergies.

Understanding Allergies

An allergy is an immune system response to a foreign substance that is generally considered harmless. The substance that triggers the reaction is called an allergen.

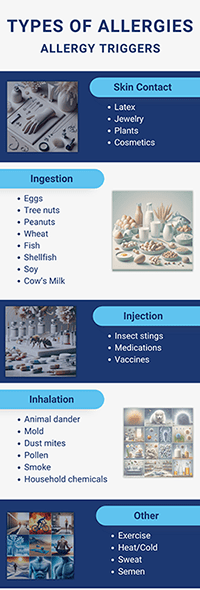

Allergens can trigger allergic responses through various routes, including:

- Skin contact

- Ingestion

- Injection

- Inhalation

Allergy Diagnosis

A correct diagnosis is crucial for managing an allergy effectively. It helps the patient know what substances to avoid. It also assists in identifying what medications could potentially aid in reducing symptoms along with lifestyle changes that may reduce exposure to allergens.

“By adopting a detective-like mindset and employing a team approach with our patients, we aim to identify true underlying allergies and, by doing so, allow a more effective way to limit bothersome symptoms and improve your overall well-being.”

–Dr. Clifford Bassett, M.D.

Allergy Testing

Blood and skin tests are the two most common ways to test for allergies. Both tests are simple and quick for allergy providers to perform.

Blood tests:

The body produces certain antibodies in response to allergens. A blood test measures the presence of these antibodies in the bloodstream. To do this, the allergy provider takes a small blood sample from the patient’s arm using a needle and test tube or vial. Overall, this process takes no more than five minutes. No special preparation is necessary for this test.

Skin tests:

A skin test involves placing a small drop of specific allergens on different locations of the skin. Then, the allergy provider lightly scratches or pricks the skin through the allergen and watches for reactions. If the patient has an allergy, a small red bump will appear within 15-20 minutes . Providers may instead inject the allergen sample just below the skin or place small patches containing allergies on the skin.

Types of Allergy Treatment

Allergies have no cure, but with treatment, patients can manage their symptoms and improve their quality of life.

Several treatments are available to manage allergies, from medications to immunotherapy to lifestyle changes. Each offers different benefits and considerations.

Below, we’ll examine common treatment types.

“Allergy medications provide quick relief from symptoms, making them suitable for various seasonal and indoor allergies.”

Allergy Medicine

There are several prescription and over-the-counter medications available to help alleviate allergy symptoms. It is best to consult a healthcare professional before using any over-the-counter medicines.

With that in mind, here are some major types of allergy medications:

Antihistamines

Antihistamines block the effects of histamines, eliminating or reducing the severity of symptoms. In general, patients must take these regularly before coming into contact with allergens per the directions to maintain effectiveness.

Many antihistamines are available over the counter and come in many forms, such as pills, capsules, chewable tablets, liquids, and nasal sprays. Some antihistamines require a prescription.

Decongestants

Decongestants can reduce nasal congestion associated with colds and allergies. They work by narrowing blood vessels, increasing the space through which air can pass in the patient’s airways .

Decongestants are available in oral (pills or liquids) and nasal spray form. Many decongestants are available over the counter .

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids relieve allergy symptoms by reducing inflammation and suppressing the immune system response against allergies.

Most corticosteroids are either in topical or oral form:

Topical:

These come as ointments, creams, or nasal sprays and suppress the body’s immune response and reduce inflammation at the application site.

Oral:

These come as pills and liquids. They are usually more potent to reduce overall bodily inflammation rather than site-specific inflammation . However, they may come with more severe side effects. Consequently, these are used in more serious cases of allergies.

Immunomodulators

Immunomodulators change the body’s immune response. Immunomodulators that suppress the immune response are called immunosuppressants — these are the kinds used for allergy patients.

Immunomodulators for allergies are typically administered orally, intravenously, or by injection .

Allergy Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a preventative approach offering more targeted treatment for allergies . The treatment involves exposing the patient to small, gradually increasing doses of the allergen to help their body build a tolerance.

Over time, this helps the body reduce the severity of allergy symptoms and provide long-lasting symptom relief. It is the closest treatment to a true “cure,” although allergies are incurable . Furthermore, it is a longer-term approach to treating allergies .

“Immunotherapy provides long-term relief by gradually building tolerance to allergens. It’s recommended for severe allergies when avoidance and medications are insufficient.”

There are two forms of allergy immunotherapy, explained below.

Subcutaneous Immunotherapy (SCIT)

SCIT involves injecting the patient with controlled, increasing doses of allergens . The aim is to desensitize the immune system to the allergen, reducing the immune response and, thus, the symptoms.

Sublingual Immunotherapy (SLIT)

SLIT involves administering controlled, increasing doses of allergens sublingually (meaning under the tongue) in the form of a dissolvable tablet or liquid. The area under the tongue has many blood vessels, allowing the allergen to quickly enter the bloodstream and bypass the metabolism.

Lifestyle and Environmental Modifications

Medications and immunotherapy can ease symptoms and enhance the quality of life in those with allergies.

Beyond these methods, patients have some control over their allergen exposure and symptoms through a few lifestyle choices:

Allergen Avoidance

Reducing allergens throughout the home can help patients avoid symptoms with as little interruption to their daily lives as possible.

Here are a few ways to create an allergy-friendly environment:

- Regular cleaning: Patients should regularly dust surfaces and vacuum carpets with a HEPA filter vacuum cleaner to remove allergens. Wash bedding in hot water as well.

- Closing windows during allergy season: Shut windows during allergy season to prevent outdoor allergens from entering the home.

- Air purifiers: High-quality air purifiers with HEPA filters can pull any allergens out of the air, further reducing the presence of allergens in the home.

- Allergy-proof bedding: Hypoallergenic bedding reduces the chance that the product causes a reaction, whereas allergy-proof bedding creates a barrier against allergens.

- Pet considerations: If pet dander is an issue, establish pet-free zones in the home and limit contact with pets where possible.

Furthermore, limiting outdoor activities during peak allergy season can reduce exposure and symptoms.

Dietary Adjustments

Certain foods cause allergic reactions. These include:

- Nuts

- Dairy

- Gluten

- Shellfish

- Soy

Furthermore, one’s overall diet can sometimes impact the severity of symptoms.

Consider making the following dietary adjustments:

- Identify and avoid allergenic foods: Consult with an allergy provider to identify which foods cause reactions, then strictly avoid them.

- Consume a healthy diet: Inflammation can impact hay fever symptom severity . Eating a healthy diet to reduce inflammation while avoiding allergenic foods for those with food allergies can potentially ease those symptoms.

- Communicate dietary needs: Communicate dietary needs when dining out or attending social gatherings. Given the prevalence of allergies, most restaurants are familiar with preparing allergy-friendly dishes.

- Read food labels: Federal law requires manufacturers to list significant food allergens on most packaged foods . Some include voluntary statements disclosing if their foods “may contain” allergens or are made in facilities where allergenic foods are handled.

- Clean food prep: Patients should wash their hands and any equipment used to prepare food. This will help remove non-food allergens remaining on the hands and prevent cross-contamination from allergenic foods.

“Overall, an Allergist can help you utilize a combination of strategies, including avoidance, medications, immunotherapy, allergen-specific treatments, and lifestyle modifications, can effectively manage allergies and improve the quality of life for sufferers.”

Get Started on Your Path to Allergy Relief

Allergies are a widespread and diverse chronic condition, but there are treatment options available to help ease the discomfort. The experienced allergy providers at Schweiger Dermatology Group provided comprehensive allergy care and can create an effective treatment plan personalized just for you. Schedule an appointment today and let the journey to better health begin.

Sources:

- Johns Hopkins, Allergies and the Immune System

- Medline Plus, Allergy Blood Test

- Medline Plus, Allergy Skin Test

- U.K. National Healthcare System, Decongestants

- Familydoctor.org, Decongestants: OTC Relief for Congestion

- Healthline, Nasal and Oral Corticosteroids for Allergies

- Healthline, What Are Immunomodulators?

- American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, Allergy Immunotherapy

- Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy, Allergen Immunotherapy

- American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, Allergy Shots (immunotherapy)

- Frontiers, Subcutaneous and Sublingual Immunotherapy in Allergic Asthma in Children

- The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Minimal persistent inflammation is also present in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Have Food Allergies? Read the Label